The software industry has standardized on open source as fuel for innovation, an engine that has enabled unprecedented product velocity across every sector. Today, 97% of all applications contain open-source components, and roughly 70% of the average codebase is built from them, with more than 900 components per application, according to the 2025 Open Source Security and Risk Analysis report.

Innovation is accelerating, but so is fragility. Every dependency added becomes a potential attack surface, and the moment a vulnerability is disclosed, automated exploitation tools and AI-driven attackers are already scanning for ways in.

In theory, defenders have a map to follow. The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) launched the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog in 2021, offering a list of vulnerabilities confirmed to be exploited in the wild. It quickly became a cornerstone of modern vulnerability management, helping overwhelmed security teams focus on what matters most: verified threats.

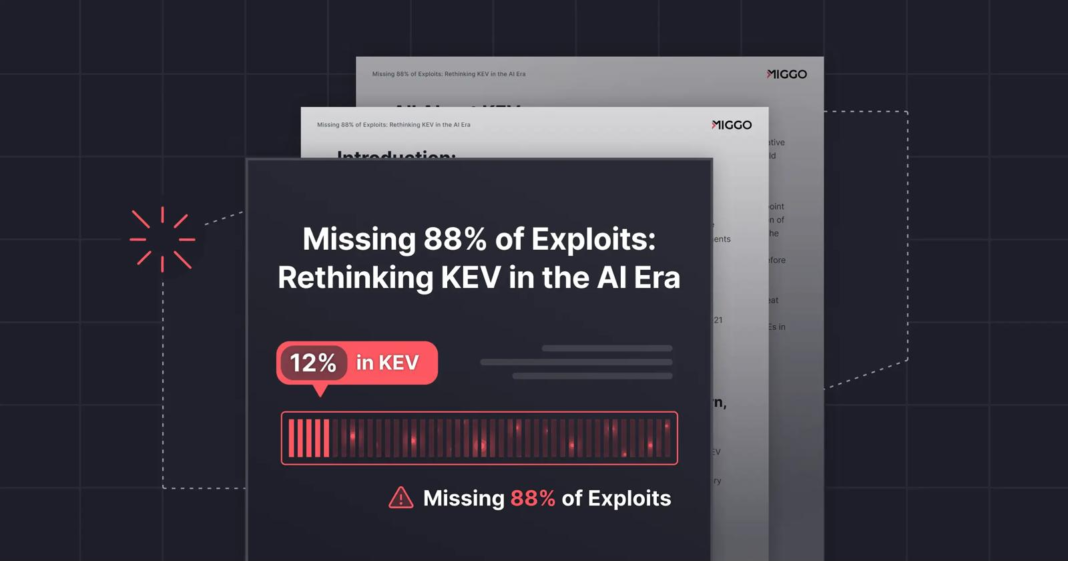

However, the premise behind KEV, of confirmation before prioritization, is becoming an Achilles’ heel. Miggo Security’s latest research exposes the scale of the problem: 88% of CVEs with publicly available exploits never appear in KEV.

What Happens When Offense Outpaces Verification

Miggo analyzed over 24,000 open-source vulnerabilities from the GitHub Security Advisory (GHSA) ecosystem, spanning npm, PyPI, Maven, RubyGems, and other platforms. The dataset revealed over 1,000 vulnerabilities that included at least one link to a GitHub-hosted exploit repository, narrowing the list further to 572 verified exploits.

The KEV comparison was stark: Only 69 of the 572 exploits identified by Miggo appeared in the KEV catalog. This means attackers have working exploit code for nearly nine out of ten vulnerabilities that do not yet exist in KEV.

Breaking down the 572 exploits makes this even clearer:

- 407 were weaponized or functional exploits, fully working attack modules requiring minimal setup

- 165 were proof-of-concept exploits

Yet only 68 of the 407 working exploits and only 1 of the 165 proof-of-concept exploits existed in KEV.

The result is what Miggo calls the KEV Gap: the widening distance between what attackers can exploit and what organizations are told is being actively exploited. As attackers leverage AI to convert new vulnerabilities into live exploits in minutes, the time it takes for a vulnerability to appear in KEV has become untenable.

If Exploitation Happens in Minutes, No List Can Be Fast Enough

This isn’t a criticism of KEV’s mission; it is a consequence of a proof-based model operating in an era when verification is slower than exploitation. Miggo notes that even though KEV intentionally focuses on incidents affecting federal and critical infrastructure, publicly available exploit code creates immediate exposure for any organization using the affected open source component.

The problem goes deeper than scale. Four forces, what Miggo calls the Four Vs, define the modern exploitation landscape:

- Volume of new CVEs

- Variants of attacks

- Velocity of exploitation

- Visibility challenges across complex application stacks

Mapping and patching every vulnerability is impossible. Patch development takes time; exploitation now takes minutes. The traditional security lifecycle of disclosure, confirmation, and patching has collapsed.

Where Live, Runtime Defense Changes the Economics of Attack

Miggo advocates a different model: proactive runtime defense, which combines predictive vulnerability intelligence, reachability analysis, and AI-generated virtual patching. Instead of reacting to published lists, the system evaluates applications in real time, identifies which vulnerabilities can be exploited in the specific runtime context, and automatically deploys mitigating controls to neutralize the exploit path.

In practice, this shortens the time to mitigation from weeks or months to seconds, shielding applications while teams work on permanent fixes. Runtime defense also sidesteps the core limitations of list-based models: it covers known, unknown, and zero-day vulnerabilities, not just those confirmed in KEV.

Miggo positions this as the only approach capable of keeping pace with AI-generated exploits. By watching execution paths instead of signatures, it adapts instantly to exploit mutations and protects applications even when no advisory, patch, or list entry exists.

Why Software Security Must Become a Live Discipline

KEV remains valuable, but it no longer defines complete risk. As Miggo’s research makes clear, relying on KEV alone means staying one step behind attackers by design. Lists react to exploitation; attackers automate exploitation. The economics of cyber offense have undergone a fundamental shift.

Protecting modern applications now requires security that operates at runtime, understands real exploitability rather than theoretical severity, and mitigates attacks the instant they emerge. Miggo’s argument is simple: in the AI era, software security cannot rely on lists; it must be implemented at execution.